I lived within 5 minutes walk from the neighbourhood of Saint-Henri in Montreal for 6 years.

During this time I walked through the neighbourhood almost everyday to go to the gym, coffee shops, bars and restaurants and to visit friends in their renovated lofts or those old worker houses with the iconic metal staircases.

Those daily walks, combined with my interest in local history, gave me a real sense of the neighbourhood’s character, its contrasts, and how it’s evolution defines what it is like to live in Saint-Henri today.

In this article, I will break down what exactly it is like to live in St-Henri. More specifically I will cover:

- Where is St-Henri located?

- What is the history of St-Henri?

- What is it like to live in St-Henri today?

- St-Henri demographics

- St-Henri commute

- Is St-Henri safe?

- What are the schools like in St-Henri?

- What is the St-Henri real-estate market like? (Q4 2025)

- Final thoughts

Where is St-Henri located?

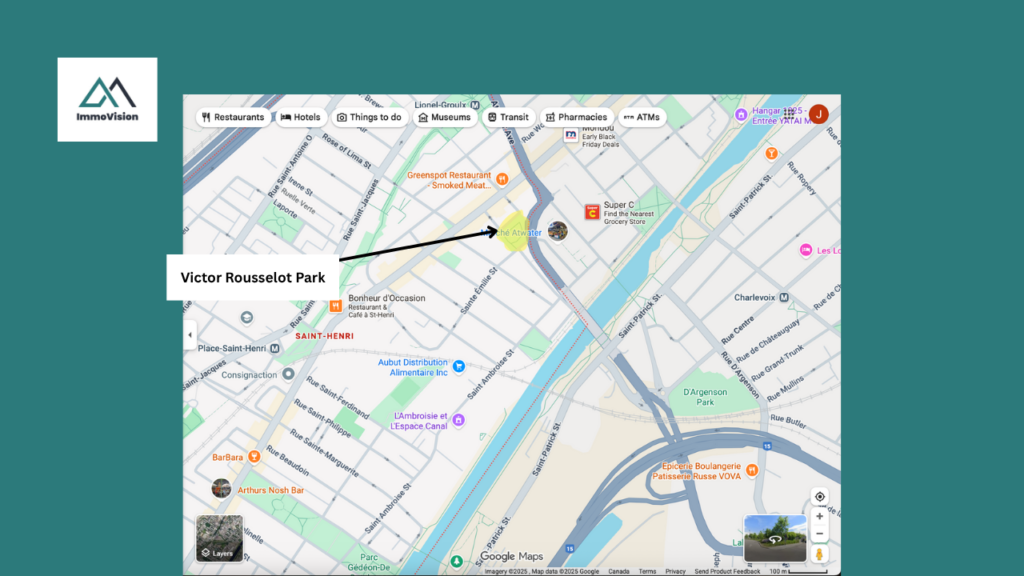

Saint-Henri is located in southwest Montreal, in the borough of Le Sud-Ouest. It is bounded by Atwater Avenue to the east, Highway 136 to the north and the Lachine Canal to the south.

What is the history of St-Henri?

The history of Saint-Henri begins in 1685 when Jean Talon, the Intendant of New France, designated the area as the site of a new tannery. This is a workshop where animal hides were cleaned, treated, and transformed into leather.

At the time, tanneries were considered “noxious trades”. They produced strong odours, generated waste, and posed fire-safety risks. For this reason, they had to be located outside of the city walls and away from the general population. They also had to be located next to running water for washing hides.

Jean Talon chose the site that is now called Saint-Henri because it was outside the city walls and sat along the Rivière Saint-Pierre. This river is no longer visible, but once flowed through what is now Saint-Henri, Little Burgundy, and Pointe-Saint-Charles.

Over time, a cluster of tanneries developed along the Rivière Saint-Pierre. This collection of tanneries that sprung up along the river gave the district its historic name, “Les Tanneries.” You can see the river in an early map of Montreal. Les Tanneries would have been built along this river.

The image below shows the area as it appeared before the 1800s. At this time it was still a rural settlement far removed from the city. What is now a ten-minute ride on the Metro from Place-Saint-Henri to downtown would, at that time, have been an arduous half-day journey on foot or by cart.

The population of the Les Tanneries grew and the community eventually requested a Catholic Parish. This parish was established in 1810 and was dedicated to Saint Henry of Bavaria. This is where the name Saint-Henri gets its name from.

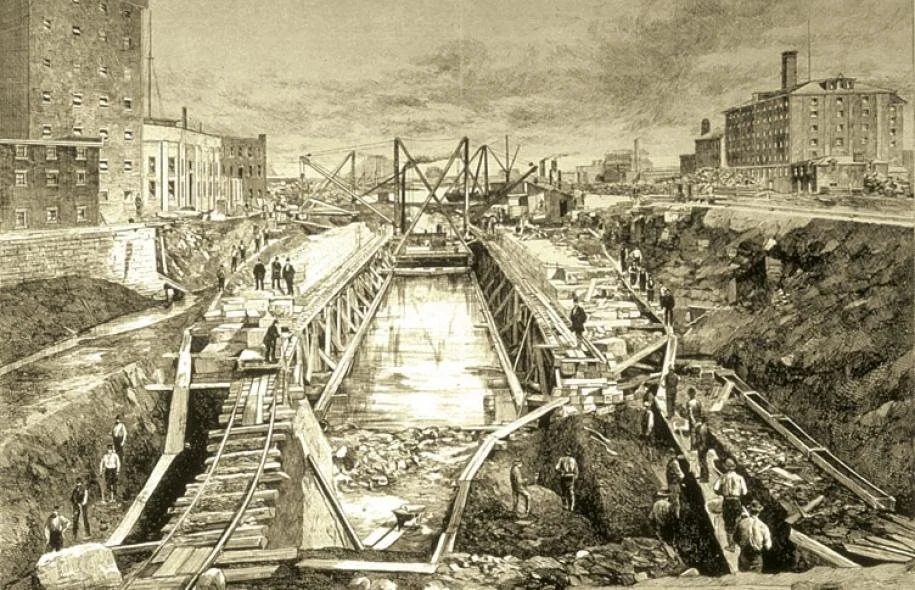

Industrialization and the Lachine Canal

The tannery district declined in the 1800s as Montreal industrialized. The small artisanal tanneries along the Rivière Saint-Pierre could not compete with new factory-scale production. The tanneries therefore moved to larger industrial sites along the St. Lawrence River and other areas better suited for factory-scale production.

During this period of time, many of the buildings, tannery pits, and cottages remained scattered along the Rivière Saint-Pierre. However, in 1821, when development of the Lachine Canal started, the population of Saint-Henri started to grow as workers came to work on the canal. In 1825, the census recorded 470 inhabitants in the village, including 147 workers.

For several decades the neighbourhood existed in-between worlds. It was part rural village and part industrial canal corridor. However, in the 1848 the canal was widened. This unlocking hydraulic power for mills and factories along its banks. Over the next 30 years, the population grew from 470 to 6,400 people. This is a growth rate of more than 1200%. All of these new residents were workers employed in the canal-side factories and transport jobs that defined Saint-Henri’s rapidly industrializing economy.

Between 1881 – 1901 the population of Saint-Henri more than tripled, going from 6,400 to 21,000 residents. This was, for the most part, caused by the arrival of more and more factories. the Merchant Manufacturing Company (which became Dominion Textile), the Williams Sewing Machine Factory, the Belding Paul silk mill, and many more. These companies created buildings that are still visible today. For example, the former Merchants Textile Mill building is now the Château Saint-Ambroise, an office space fro small businesses and an event spaces.

Workers from across Quebec and beyond came to Saint-Henri, drawn by the promise of steady work in the factories. Real-estate developers responded to the expanding population by building dense rows of inexpensive wood-frame dwellings close to the plants. These offered low cost housing for factory workers moving to Saint-Henri.

On streets like Beaudoin, St-Ferdinand, Delinelle, and Turgeon, you can still see these late-19th-century wooden houses hidden behind thin brick facades. They remain some of the strongest architectural reminders of Saint-Henri’s working-class origins.

By 1901, Saint-Henri had one of the densest concentrations of industrial employment in Quebec. It was also heavily indebted and unable to fund modern infrastructure for its fast-growing industrial population.

At this point, Montreal, was already expanding outward. The city offered better public services, infrastructure and financial stability because it had a larger tax base. As such, St-Henri incorporated into the City of Montreal in 1905. Later on, in 1960s urban renewal era, the neighbourhood of St-Henri was split into up urban planners creating the neighbourhood of Little Burgundy. In 2002 both Saint-Henri and Little Burgundy were incorporated into the modern borough of Le Sud-Ouest.

What is it like to live in St-Henri today?

Today Saint-Henri has the look and feel of a patchwork city.

Walk down Notre-Dame Street and you’ll find a 1920s brick triplex next to a modern condo. Or the 1825 Lachine Canal running alongside a 1950s factory now retrofitted into offices for today’s creative and tech workers. This visible layering of different eras is a big part of what gives Saint-Henri its unmistakable charm.

The most recent wave of change in Saint-Henri is the arrival of gentrification. Young working professionals have moved into the neighbourhood for its proximity to downtown, walkable streets, and a sense of community. Their arrival has pushed property prices upward and fuelled a surge of redevelopment. Most noticeably, along the canal, mid- and high-rise condo projects now stand where old industrial buildings once operated.

The architecture and layout of Saint-Henri creates a 19th-century working-class atmosphere. The narrow streets, small apartments, brick triplexes, and rows of local shops and cafés. All of this encourages daily life to spill out onto the sidewalks. In the summer you will find people sitting on their front steps, chatting with neighbours and using the parks and canal paths as extensions of their living space. Whilst year round, you will see people walking to local coffee shops, restaurants and bars. This is very much the way working-class communities functioned here a century ago.

Of course, most residents today don’t live anything like the factory workers who once filled the neighbourhood. But the physical setting still shapes the mood of the place. This is very different to the traditionally wealthy areas like Westmount to the north, where the properties are noticeably larger and more spaced out.

Saint-Henri is also incredibly well situated for anyone who loves being outdoors. On a bike, you can ride the full length of the Lachine Canal, passing parks, green spaces, and café patios along the way. The neighbourhood also has several local parks, as well as an outdoor swimming pool and splash pads that comes alive in the summer months.

All of this makes Saint-Henri a naturally walkable, outdoorsy place. This reinforces the neighbourhood’s working-class feel and helps build a strong sense of community. The kind of place where you see your neighbours and know the people on your block.

Lastly, 25.6% of occupied housing units in Saint‑Henri (2014 data) were social or community housing. These properties are concentrated around Delinelle, Ste-Marguerite, St-Jacques, the area near the Lionel‑Groulx station, and the older industrial blocks. This creates a mix of people and incomes. This can make also make things feel a bit rougher. However, the area is still considered safe by locals and it is worth remembering that many of these people have lived here longer than those who came with the new wave of gentrification and care deeply about their community.

St-Henri demographics

Over the past two decades, Saint-Henri’s demographic profile has shifted in ways that reflect gentrification.

According to the 2021 Census, the population stood at 5,813, up 3.6% since 2016.The proportion of adults aged 25–64 holding a bachelor’s degree or higher, however, remained relatively low at 15.4%, compared to the provincial average of 29.5%.These statistics show a rising population, but still modest educational attainment. This suggest a neighbourhood in transition.

Furthermore, Saint-Henri has an unusually large concentration of young adults aged 25–34 (27.1%), far above the Montréal average (17%), and nearly half of all households (48%) are single-person households. Couples without children make up about 49% of all families, meaning the neighbourhood is dominated by young singles and child-free couples. This is a typical demographic signature of early-stage gentrification.

Income patterns point in the same direction. Employment income data shows growing numbers of residents earning over $60,000, while the share of workers earning between $20,000-$59,999 is declining. Combine this with real-estate and housing trends where the worker-era wood-frame homes are being renovated, old factories converted to lofts, and trendy amenities appearing on Notre-Dame Street, and you can clearly see the transformation.

Saint-Henri is shifting from a historic working-class industrial district into a mixed and increasingly middle-income neighbourhood.

St-Henri commute

In this section, we look at what it’s like to commute in Saint-Henri using the three main ways people get around:

Car

Driving in Saint-Henri can be a mixed experience depending on where exactly you live. Streets closer to the Lachine Canal, Notre-Dame Street, and Atwater Market are feel busy during peak hours either with pedestrians or cars. But the interior residential streets are calmer and easier to navigate. Most homes are older duplexes and triplexes with laneways, and you’ll find a decent amount of on-street parking (though winter restrictions apply).

Saint-Henri has good road connectivity. Because it sits just west of downtown and directly south of the Ville-Marie Expressway, you can reach major routes quickly, including:

- Highway 20 (toward the West Island, Dorval, and the airport)

- Highway 720 / Route 136 (Ville-Marie Expressway into downtown)

- Atwater Avenue / Guy Street (direct north–south access to Westmount and downtown)

- Notre-Dame Street (east–west connector through Le Sud-Ouest)

From Saint-Henri, you can drive to Westmount, Little Burgundy, Pointe-St-Charles, Verdun, NDG, and downtown in a matter of minutes. There is also good access to Communauto, which many residents use instead of owning a vehicle.

Public transport (metro and bus)

Saint-Henri has excellent public transit, which is one of the main reasons it attracts so many young professionals.

The neighbourhood is centred around Saint-Henri metro station (Orange Line), with most homes located within a 5–15 minute walk. For many residents near Atwater Market or closer to Little Burgundy, the Lionel-Groulx interchange is also easily accessible. This is a major bonus because it connects both the Orange Line and Green Line, will take you directly to Montreal’s Gare Central (central station) for national travel and offers direct buses to the airport via the 747.

Across the neighbourhood, frequent bus routes run along Notre-Dame, Atwater, and Saint-Jacques, providing quick connections to:

- Downtown

- Westmount

- Verdun

- Little Burgundy / Griffintown

- Atwater Market

- MUHC (Glen) superhospital

Public transport coverage is denser than in Pointe-St-Charles and is often faster than driving during rush hour because the metro is so close and frequent.

Bike

Saint-Henri is one of Montréal’s most bike-friendly neighbourhoods, especially if you live near the Lachine Canal.

The Lachine Canal bike path runs along the entire southern edge of the neighbourhood, offering a safe, car-free route to:

- Atwater Market (2–5 minutes)

- Little Burgundy / Griffintown (5–10 minutes)

- Old Port (10–15 minutes)

- LaSalle / Verdun (15–20 minutes)

Within Saint-Henri itself, cycling is practical for everyday errands because the neighbourhood is flat, compact, and filled with BIXI stations. This is particularly around the metro, parks, the market, and Notre-Dame Street. Many residents choose to bike for most of the year because it is often faster than driving and avoids the congestion that builds up near Atwater and the market.

Overall, Saint-Henri offers one of the most balanced and versatile commuting experiences in the southwest. Whether you drive, take the metro, or cycle along the canal, getting around is fast, convenient, and well-connected to the rest of the city.

Is St-Henri safe?

According to SPVM data for Police Station 15, which covers Saint-Henri along with a few neighbouring districts, the area recorded about 42 crimes per 1,000 residents in 2021, roughly 14% higher than the Montréal median. Crimes against the person were also somewhat higher than average. At the same time, overall crime in the sector has fallen by nearly 20% over the last decade.

In practical terms, Saint-Henri feels like a typical inner-city Montréal neighbourhood. It is generally safe for day-to-day life, but a bit more gritty around the metro stations and older industrial pockets than in fully gentrified areas like Griffintown or leafy, upscale Westmount.

In my own opinion, and with no real data to back it up. I found the area around Victor Rousselot Park particularly unsafe. This area contains a shelter for unhoused people and a supervised drug use site. As such, you will see syringes on the floor and lots of homeless people occupying park benches. A short walk up the road is Lionel Groulx metro, which also feels quite unsafe, especially at night.

What are the schools like in St-Henri?

St-Henri has three French speaking primary schools (École primaire Victor-Rousselot, École primaire Ludger-Duvernay and École primaire Saint-Zotique) and one secondary school (École secondaire Saint-Henri), all within walking distance for families who live in the area. There are no English speaking schools in the area however, there are several nearby English-language and private schools in Westmount, Petite-Bourgogne, and Pointe-St-Charles serve local students that qualify for French language education under Quebec’s Bill 101.

Bill 101

– they have a parent who received the majority of their schooling in English in Canada and,

– that parent is a Canadian citizen,

– or the child already has a sibling who attended English public school in Canada.

In Saint-Henri, the local public schools face meaningful challenges. For example, École secondaire Saint-Henri received a score of 4.0 out of 10 in the 2024 provincial ranking, placing it among the lower-performing schools in Québec. At the primary level, schools like École primaire Victor-Rousselot and École primaire Saint-Zotique serve communities with higher socio-economic needs (indices of ~40 and ~30 respectively). This often correlates with added educational obstacles. What this means for families is that you may want to look closely at program offerings, support services, and student-teacher resources if you prioritize academic performance.

What is the St-Henri real-estate market like? (Q4 2025)

The table below shows estimated property prices in Saint-Henri for Q4 2025.

| Property type | Typical price range in Saint-Henri (Q4 2025, est.) |

|---|---|

| 1-bed condo | $400,000 – $460,000 |

| 4-bed (3–4 bed) condo | $700,000 – $850,000+ |

| Duplex | $800,000 – $1,000,000 |

| Triplex | $1,100,000 – $1,300,000+ |

| Townhouse | $650,000 – $750,000 |

Final thoughts

I lived near Saint-Henri, and I found walked into the neighbourhood almost every day to go to the gym for 3 years. What always struck me was how much renovation was taking place. New sidewalks along Notre-Dame, updated storefronts, a lot of fresh brickwork on buildings that had clearly been through several lifetimes. But just as often, you get the sense that there are a lot of gaps in the area. Empty stretches where everything suddenly went quiet for a few blocks, lots of abandoned buildings and closed businesses that had been made obsolete by the rising tide of gentrification.

For me, this is the real picture of Saint-Henri. It’s a place in continual change, and unlike some neighbourhoods where transformation feels cohesive, here it happens in a much more fragmented way. This isn’t like Pointe-St-Charles, where there’s a strong sense of collective rooting of families, community, and shared history that hold the place together. Saint-Henri feels more like a neighbourhood of two halves, living side by side. There’s a visible tension between old and new, between what the area was and what it’s becoming, and that tension is almost built into the streets.

But that’s also what gives Saint-Henri its character. It has always been shaped by struggle, reinvention, and the push-and-pull of growth. It doesn’t present one single identity, it holds several at once. And that unfinished, evolving quality is exactly what makes it so compelling. It’s honest. It’s raw. And it’s a neighbourhood that tells the story of Montreal’s past and future at the same time.